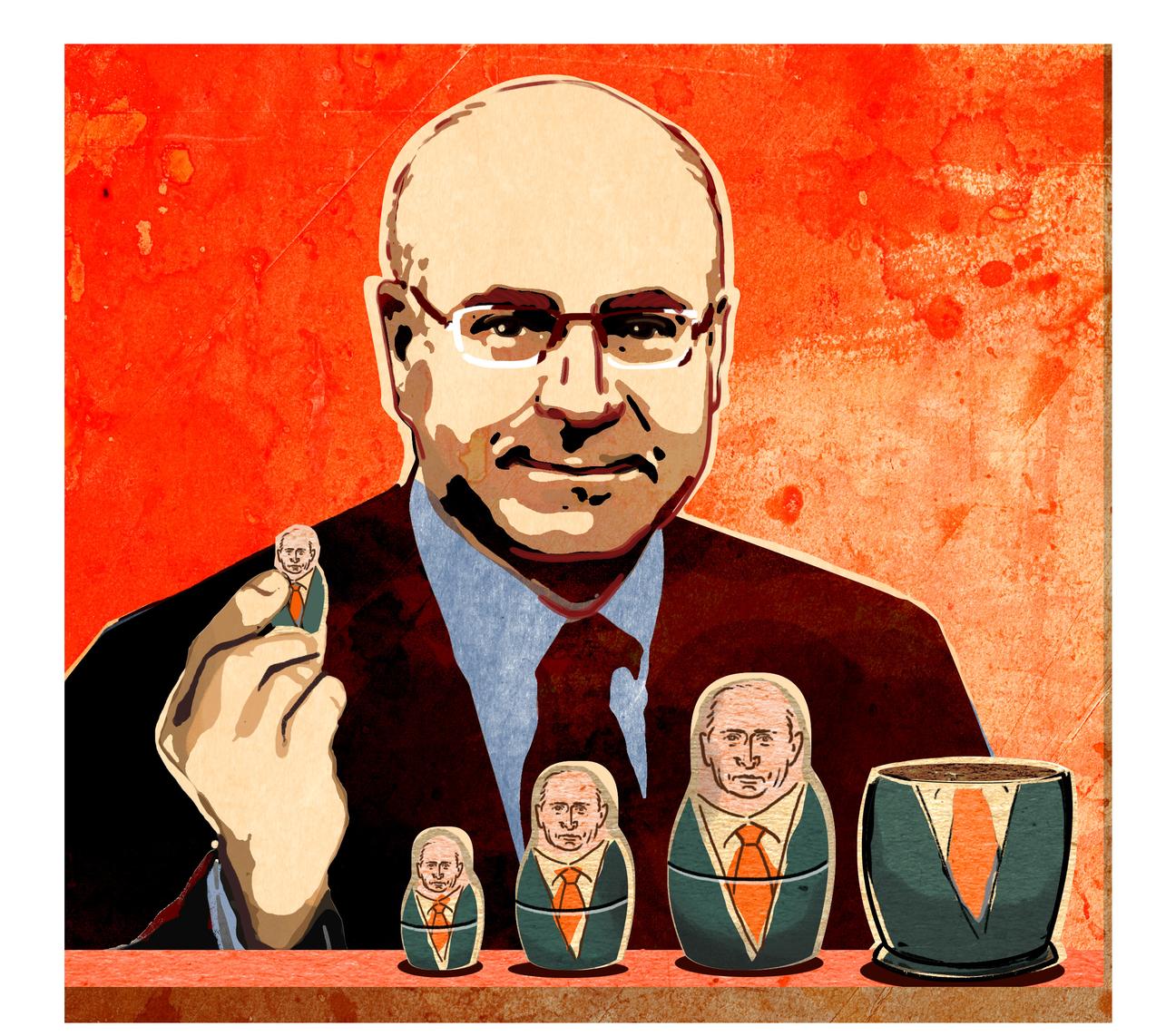

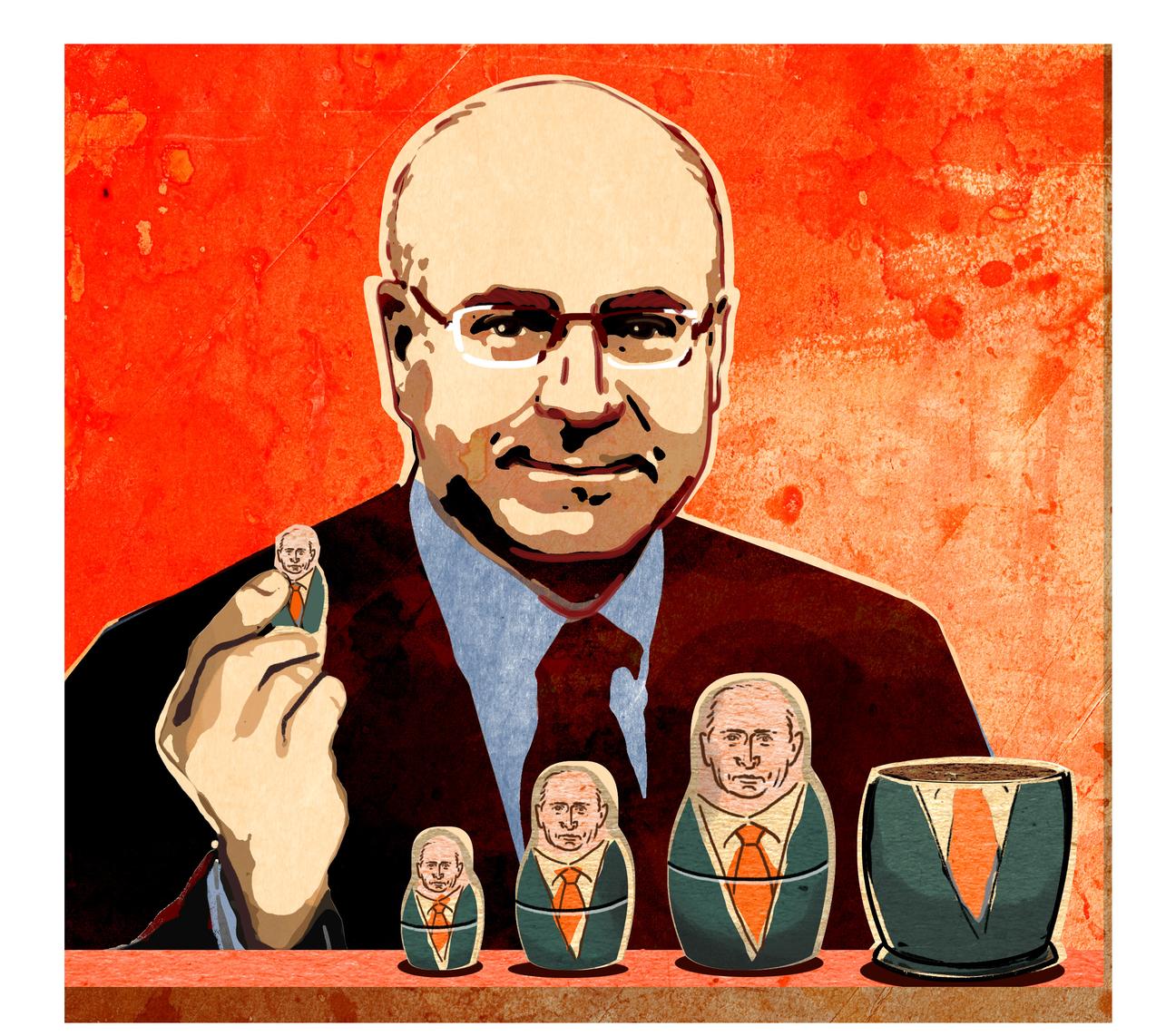

Anti-Putin crusader Bill Browder on his disillusionment with Moscow’s leader and his tangles with the man behind the Trump dossier.

hicago

On the elevator to his hotel suite, Bill Browder has his nose pressed to his cellphone. “I’m checking for updates from Guatemala,” he tells me. Not for the latest coffee prices or vacation rentals, but for news of a Russian family imprisoned there “for violations of local residency laws—all because of pressure from the Putin regime.”

The Bitkov family is Mr. Browder’s latest moral campaign. An Anglo-American businessman with deep and harrowing ties to Russia, Mr. Browder is arguably the man Vladimir Putin would most like to see go up in a vengeful puff of smoke. Once the largest private investor in Russia, he has become—since his 2005 expulsion from the country and the 2009 death in prison of his lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky —Mr. Putin’s most vocal civilian opponent in the Western world.

In February 2015, Mr. Browder published a book called “Red Notice,” an account of the murder of Magnitsky, who was beaten to death in his cell by Russian riot police. “People started writing to me,” Mr. Browder says. “Some said, ‘I love your book’; others said they hated it. One even wrote to me saying the CIA had installed devices in my teeth that listened to my thoughts, and that he could help me remove them.”

A more credible email came from a Russian woman who described what had happened to her and her husband. “She said they were greatly moved by the Magnitsky story, and were suffering from a similar ordeal,” Mr. Browder says. So he decided to help.

As Mr. Browder tells it, this was Irina Bitkov’s story: Her husband, Igor, owned a profitable pulp mill near St. Petersburg. A local oligarch coveted the business and made Mr. Bitkov an offer. After he demurred—the suggested price was derisory—the Bitkovs’ teenage daughter, Anastasia, was abducted and raped. Then Mr. Bitkov’s bank (owned by a Putin crony) called in its loans, forcing the mill into bankruptcy. Fearing for their lives, the Bitkovs fled, ending up in Guatemala, which has no extradition treaty with Russia. They obtained legal residence in 2009 with the help of a Guatemalan law firm.

Six years later, a local United Nations-funded anticorruption commission charged the Bitkovs with human trafficking, based on alleged “passport violations.” It was “a wildly improbable charge,” Mr. Browder says, “brought under pressure from the Russian bank that had foreclosed on them.” Mr. and Mrs. Bitkov were sentenced to 19 and 14 years in prison, respectively, “a worse sentence than if they’d committed rape, or assault, or armed robbery.”

Given the punishment already inflicted on the Bitkovs, why would Mr. Putin’s forces bother to continue their vendetta? “I’ll explain it to you,” Mr. Browder says, now animated. “It’s all about example-making. The reason why they did it is so that the next person they go to in Russia, to ask him to turn over his business, doesn’t say ‘no.’ If he says ‘no,’ they’ll say, ‘It doesn’t matter where you go. We’re going to take your stuff, we’re going to hunt you and your family down, we’re going to ruin your lives. Look at the Bitkovs.’ ”

Mr. Browder pivots to the story of Sergei Magnitsky: “They made an example of him, too—telling idealists everywhere in Russia that ‘we’ll kill you.’ ” Magnitsky was the man who transformed Mr. Browder from an energetic and largely unfussy participant in Russia’s markets to a crusader at war with Mr. Putin. It happened this way: Mr. Browder was the founder of Hermitage Capital, which was among the largest portfolio investors in Russia. Magnitsky, a Moscow lawyer, worked on a contract for Mr. Browder beginning in October 2007.

In the course of his auditing, Magnitsky uncovered a theft from the Russian treasury of past taxes Hermitage had paid, amounting to $230 million. When he refused to back down from his sleuthing, Magnistsky was arrested in November 2008. He died after 358 days in prison. Mr. Browder’s subsequent lobbying prompted Congress to pass the Magnitsky Act of 2012, designed to punish any Russian official who had been involved in the lawyer’s death.

“Sergei was an idealist—a naive idealist,” Mr. Browder says. “Russia has created a system where evil people get rewarded and good people get crushed. It’s almost like the Soviet Union all over again.” Back then, if you weren’t a member of the Communist Party, “you were excluded from all privileges. Now, if you’re not a member of the criminal enterprise, you’re excluded from all the valuable things in life.” By “the criminal enterprise,” Mr. Browder means the Putin regime: “The mistake everybody makes about Russia is they think there’s the mafia and there’s the government. It really is one and the same thing.”

When Mr. Browder first went to Russia, in 1995, Boris Yeltsin was president and the country was in a state of amoral chaos. “Twenty-two oligarchs,” he says, “ended up with 40% of the country. Everyone else lived in destitute poverty, with professors driving taxis and art museums selling paintings off the walls.” Mr. Browder acknowledges his own motives weren’t idealistic. “I went there,” he says, “as a capitalist and an opportunist. There was a huge market opportunity, which was that stocks were trading at this enormous discount.”

But what was happening in Russia soon began to disturb him. “Long before the Magnitsky story, I saw this looting going on,” he says. “I would see very brazen theft from my own companies.” This upset him “from an economic standpoint.” But more than that, it seemed “so fundamentally wrong that there was just this total apathy about it.”

What followed was “a growth of revulsion within me.” He attributes the shameless stealing in the Yeltsin years to a continuation of old Communist-era habits. There were “no moral boundaries—the result of getting rid of religion. There was no ‘Thou shalt not steal’ or ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ ” So when Mr. Putin came to power in 2000, Mr. Browder was enthusiastic.

“First of all,” he says, “Putin wasn’t drunk. He seemed reasonably fit. He spoke a bit of English and seemed to be a technocrat. And then he said all of these things that sounded good, like, ‘We’re going to bring the chaos to an end,’ and, ‘We’re going to end all this oligarch criminality.’ ” Mr. Browder liked the spiel: “It was attractive. You wanted to believe him. It seemed plausible, and for a brief period of time he was actually doing the things that a person with those intentions would do.” Mr. Browder adds that “no one will admit it today. I’m the only one who says openly that I was pro-Putin until I wasn’t.”

When was the Damascene moment when Mr. Browder saw that Mr. Putin wasn’t a force for good? “I don’t think there was a moment per se,” he says. “There was a sort of slow deterioration in my impression of him, which eventually came to a full-on conclusion.” Mr. Browder had cheered when Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Russia’s richest oligarch, was arrested in 2003. “Khodorkovsky was my biggest nemesis,” Mr. Browder says, “and I was fighting with him over all sorts of problems at Yukos,” Mr. Khodorkovsky’s oil company. “I owned shares of Yukos and Yukos subsidiaries, and he did all these illegal tricks to reduce the value of those shares so that he could buy it all back.” (Mr. Browder says he has “fully forgiven Khodorkovsky,” who was freed in 2013 and has always maintained his prosecution was politically motivated. “We’re on the same side of the barricade, fighting against Putin.”)

What made Mr. Browder lose faith was the failure to prosecute another oligarch for practices similar to those of which Mr. Khodorkovsky had been accused: “I thought to myself, wait a second. How does this work? How does this fit into that game plan of going after the oligarchs?” That was when he says it “became clear that Putin wasn’t sincere. His intention wasn’t to get rid of the oligarchs. It was to become the biggest oligarch himself.” By arresting Mr. Khodorkovsky, Mr. Browder says, the regime had made an example, ensuring that every other oligarch in the land would capitulate: “Everyone started to ask, ‘What do we have to do to make sure we don’t end up like Khodorkovsky?’ ” Mr. Putin’s answer, according to Mr. Browder, was: “Give me 50% of your assets.”

Mr. Browder also contends that Mr. Putin benefited personally from the tax fraud Magnitsky uncovered: “When the law was in its final version, he issued a public statement saying that his single-largest foreign-policy priority was to stop the Magnitsky Act from becoming law.” Why? “The first and most specific reason,” Mr. Browder says, “and we only know this now, is that Putin actually received some of the proceeds of the crime that Sergei was killed over. In theory—and Putin saw this—he could be a person put on the Magnitsky list.”

The second reason is that the Magnitsky Act establishes a template to deal with human-rights violations that “flips the old concept of sanctions on its head,” Mr. Browder says. “It targets the perpetrators—the financial and juridical elites—and not an entire country. You can’t travel. You can’t move your money around. It’s like modern-day cancer treatment targeting only the bad cells.”

The law—and Mr. Browder—featured most recently in the drama surrounding the Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya, who in June 2016 met with representatives of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. The story also involves Fusion GPS, the Washington-based opposition-research firm contracted by Hillary Clinton’s campaign and the Democratic Party to investigate Mr. Trump’s possible Russia connections.

“Putin hates the Magnitsky Act, as we know,” Mr. Browder says, “and looks for different ways to stop it. And one of his projects—well-resourced, with millions of dollars—was Veselnitskaya. She was deputized for this project because she represented the Katsyv family—Putin cronies caught up in laundering some Magnitsky money in the U.S. Some of that money enabled the purchase of apartment buildings in New York by Denis Katsyv, whose father is a government official close to Putin.” (In May 2017 Mr. Katsyv’s company, Prevezon Holdings, reached a $5.9 million settlement with the U.S. government, thereby avoiding a trial. The company and the Katsyvs denied any wrongdoing.)

In Mr. Browder’s account, Ms. Veselnitskaya came to America on behalf of the Katsyvs when the U.S. Justice Department began a forfeiture order for the properties. Ms. Veselnitskaya then began “a legal campaign to extricate the Katsyvs” from the case “and a political campaign to repeal the Magnitsky Act.” She hired John W. Moscow, a lawyer with the firm Baker Hostetler, who “brought Glenn Simpson on as part of their team” in 2014. In his testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee last August, Mr. Simpson, Fusion GPS’s founder and a former Journal reporter, said his firm provided litigation support to Baker Hostetler in the Prevezon case. Mr. Browder says that Mr. Simpson “got very energized in the spring of 2016 and basically started to work on behalf of Veselnitskaya, who has since been shown to be a Russian agent.”

Mr. Browder is referring to Ms. Veselnitskaya’s public acknowledgment that she is “an informant” for the Russian prosecutor general’s office. “That makes her an agent,” Mr. Browder insists. “So Glenn Simpson was working, effectively, also as an agent for the Russian government, as an adjunct to the Russian FSB,” the KGB’s successor. “At the same time . . . he’s doing this project to create a dossier on Trump.”

Mr. Browder tells me he heard from reporters that as the campaign against the Magnitsky Act proceeded, Mr. Simpson was pitching a story that “Magnitsky wasn’t murdered, he died of natural causes,” that “Magnitsky wasn’t a whistleblower, he was a criminal,” and that “Bill Browder telling this story is in contempt of Congress and perjuring himself.” (Through a lawyer, Mr. Simpson declined to comment. In November Mr. Simpson testified before the House Intelligence Committee: “I obviously think Sergei Magnitsky was killed in prison by neglect, if not worse.”)

Three days before Mr. Putin’s fourth inauguration, I ask Mr. Browder about the Russian president’s future. “We have Putin 4.0 now,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if it’s his fourth or fifth term. None of the mechanical electoral processes are relevant.” There are, Mr. Browder says, only three ways it can end: “One, he’s killed in office. Two, he’s overthrown. And three, he dies of natural causes.”

Mr. Browder’s bet is on natural causes: “He will stay in power till he dies. That’s the only way he can protect his money.”

Mr. Varadarajan is a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.