The ordeal of a Russian family

Guatemala City

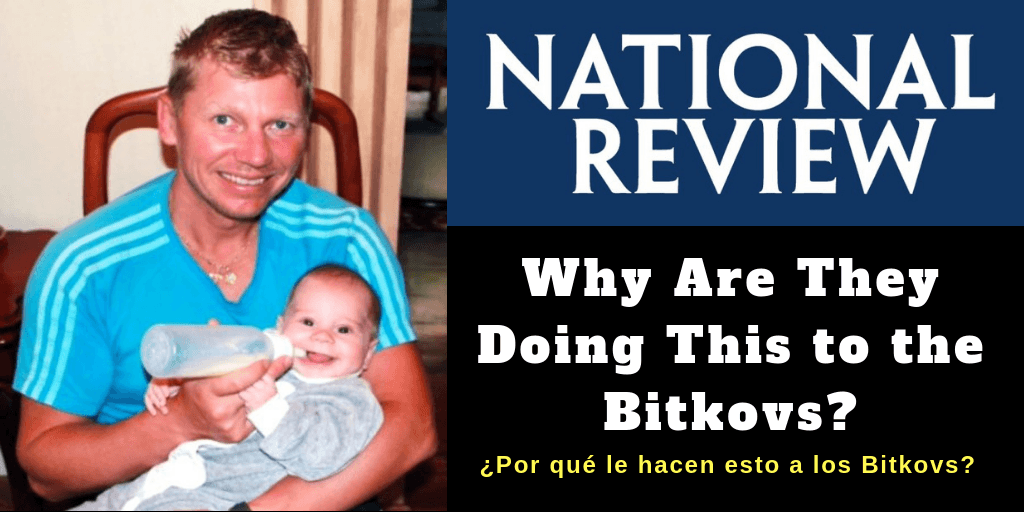

You should know about the Bitkovs — a strange and terrible case. The Bitkovs are a family of four: Igor and Irina and their children, Anastasia and Vladimir. They started out in Russia — or rather, three of them did. Vladimir was born here in Guatemala.

Igor, Irina, and their daughter were forced to flee Russia, as so many are. They came to Guatemala to start a new life. They are now in prison here. Igor is in a men’s facility and his wife and daughter are in a women’s facility, less than half a mile away. They are forbidden to see one another. That is, Igor may not see Irina and Anastasia, and vice versa.

Vladimir, age six, is in the care of guardians (loving, selfless ones). “If I were not a child, I would be in prison too,” he says. He would rather be. He would like to be with his family, free or not. He speaks of hiding in their bedsheets.

According to the family and its supporters, the Bitkovs are the victims of a vengeful Russian state, working in curious partnership with Guatemalan authorities and a U.N. agency. Their case is all over Russia’s state media, as the Kremlin cackles at their plight. In America, Mary Anastasia O’Grady of the Wall Street Journalhas written about them repeatedly. Members of Congress are interested in holding hearings.

On April 27, there will be a hearing before the U.S. Helsinki Commission, in Washington.

The Bitkov family merits a book, rather than an article such as mine. They could be a movie, too — harrowing, Kafkaesque. I will tell their story in brief.

Igor grew up in Novodvinsk, a town in Arkhangelsk Oblast, in northwest Russia. His parents were engineers, working in a pulp and paper mill. His father was the Communist Party representative in the mill. (These were Soviet times, I should note.) Irina grew up in the city of Arkhangelsk, about 15 miles from Novodvinsk. Her father was a systems engineer, and her mother worked in a pharmacy.

Neither family had much money, but they got by.

Igor and Irina met in 1989, when Irina was visiting Novodvinsk. (Irina remembers the day precisely: September 1.) Irina and a friend were sitting on a stoop. A guy next door, Igor, was taking out the garbage. He said to Irina, “You’re not from here. I know all the pretty girls in this town, and I’ve never seen you before.” They were married nine months later. Igor was 21 and Irina 20. They are now in their late 40s.

Apparently, they are natural entrepreneurs. By dint of their own efforts and talents, starting from nothing, they built a splendid company: NWTC, for “North West Timber Company.” They dealt in pulp and paper. They pioneered clean technology, which was very important to Igor. “In my hometown, many people died from consequences of dirty technology.”

The Bitkovs were also philanthropists, funding churches and orphanages, etc. PricewaterhouseCoopers, among others, honored them for their achievements.

As their company grew, they borrowed money from three state banks: VTB, Sberbank, and Gazprombank. Sberbank would value NWTC at $428 million. Igor says it should have been more like $450 million, but let’s not split hairs.

With success came trouble — because the Kremlin and its oligarchs wanted in on the action. A leader of Sberbank wanted to buy 51 percent of the company. Putin’s party — United Russia — wanted Irina to be one of its regional chiefs. An association of businessmen, chaired by the VTB honcho, wanted her to join. (That would have entailed hefty “dues” payments from the Bitkovs.) On it went.

And the Bitkovs said no. Why? “Why did you not play ball, like everyone else?” I ask. “Principle,” says Igor. “I could have paid, no problem — but I didn’t want to. We did not want to play their game; we wanted to play ours.” Irina explains, “There is no middle way in Russia.” Either you’re in or you’re out. You can’t finesse the system. If you go along with the oligarchs, even a little, they will own you. Your hands are either clean or dirty. You can’t be a little bit pregnant. There is no middle way.

“I thought we could remain independent,” says Irina. “We were doing so much good for society. I thought that would be enough. I did not realize that not working with the government would be fatal to us.”

Putin’s Russia, in short, is a mafia state. The Bitkovs refused to pay protection.

Igor makes an additional point: “Our company showed that a private enterprise could be better run than a state enterprise. They hated me for that. We built the company from the ground up, all by ourselves. We had no government support — not from Yeltsin, not from Putin. And the results were impressive.” Irina, for her part, remembers a government official at a ribbon-cutting ceremony, for a new Bitkov factory. He said, with sarcasm, not admiration, “Evidently, it is possible to build such a company in Russia on your own initiative.”

In June 2007, something evil happened: The Bitkovs’ daughter, Anastasia, age 16, was kidnapped, drugged, and repeatedly raped. This took place over the course of three days. Who did it? “A criminal structure, working with the FSB,” Igor explains. “One with impunity.” (“FSB” is the new name for “KGB.”) Igor paid a ransom of $200,000, in cash. He handed over the money — dollars — to the police, acting as “middlemen.”

Anastasia emerged from the ordeal with severe mental problems. She has been diagnosed as “bipolar” and “borderline.” Several times, she has tried to kill herself. Yet she is much better today, and she is a very brave woman. More on this in a moment.

The attack on Anastasia was a warning to Igor and Irina Bitkov: Play ball, or else. Faced with yet more threats, the Bitkovs finally fled, in April 2008.

Immediately, the banks called in their loans. They gave the Bitkovs 48 hours. The Bitkovs had a perfect credit record — but they could not repay the balance of their loans in two days. So the banks forced them into bankruptcy and gobbled up the company they had built.

In Turkey, Igor had a phone call with FSB agents. It was the kind of phone call you don’t forget. They demanded that he return to Russia. Igor refused, fearing the worst. They then said that, wherever he and his family went, the FSB would hunt them down and kill them.

What were Igor’s options? Apply for political asylum in the United States? There was the problem of a visa, or the lack of one. How about an EU country? As Igor explains, relations between the West and Putin’s Russia were much warmer in 2008 than they would be later. (He cites Germany, in particular.) He knew of Russians who had applied for asylum in the EU and were deported back to Russia — much to their sorrow. Also, Igor was an entrepreneur, not a political figure, so how much sympathy would he get, asking for asylum?

He searched the Internet — and found a law firm called Cutino International, offering immigration services in Latin America. Igor thought first to go with his family to Panama — but Panama required a visa. Guatemala did not. So, in April 2009, they came here.

Cutino’s price for the facilitation of a Guatemalan passport and ID card was $50,000. Igor paid for three sets: for Irina, Anastasia, and himself. The documents were issued by the relevant government offices.

Obviously, it was hard for Igor to leave everything behind — even his name (he adopted a new one, the better to get lost, so to speak). But he felt he had no choice. He had one object in mind: the survival — the physical survival — of his family.

What would you and I have done, in his shoes?

The Bitkovs settled in, as best they could. They learned Spanish. The second child, Vladimir, was born in 2012 (21 years after the first!). As years went by without incident, the family felt more secure. Anastasia tried making a reality-TV show. Life was normal, relatively speaking.

But in 2013, one of the banks, VTB, having traced the Bitkovs, went to the Guatemalan authorities. The bank persuaded them to investigate the family for financial crimes. The aforementioned VTB “honcho” — Andrey Kostin, the bank’s chairman and CEO — gave power of attorney to Henry Comte, of the Guatemalan firm Comte & Font. Henry Comte is also an alternate judge in one of the courts involved in the Bitkovs’ case.

(I e-mailed Mr. Comte on April 19 to ask about this apparent conflict of interest and about the sentencing of the Bitkovs. He responded the next day, saying that the managing partner of the firm would get back to me as soon as possible. As of the time of writing, the managing partner had not.)

For more than ten years now, Guatemalan authorities have worked alongside CICIG, a U.N. agency created to fight corruption in this country. “CICIG” stands for “Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala,” or “International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala.” CICIG is highly controversial in this country. Some people think the commission is above reproach, a godsend to Guatemala. Others think, or fear, that corruption has infiltrated the corruption-fighter.

In the eyes of some, VTB and CICIG appear to be in alliance, and that would be curious indeed. VTB has long been under sanction by both the United States and the European Union. Earlier this month, Chairman Kostin was placed under U.S. sanction personally.

CICIG strenuously denies any alliance between itself and VTB, or any relationship with the bank at all.

VTB’s charges of financial crimes went nowhere in Guatemala. (And to say “VTB’s charges” is really to say the Russian state’s charges.) Those charges were patently absurd. But the authorities had another angle: passport violations, documentary irregularities. For a time, VTB was a plaintiff in a passport case, which was odd.

Mind you, CICIG and Guatemalan law enforcement were chasing some very bad actors: corrupt government officials and human traffickers, a.k.a. coyotes. There was a ring of these people. Truly nasty characters, the kind to murder whistleblowers, some of them. But did Igor, Irina, and Anastasia Bitkov belong in the same net?

On January 15, 2015, at 6 in the morning, they were arrested. A full 70 agents came to the Bitkovs’ house. Another 30 went to the family office. Still another 30 went to the house of Anastasia’s boyfriend. That’s 130 agents in total — an impressive number for a passport case.

Initially, the Bitkovs were kept in carceletas, or cages, in humiliating and dangerous conditions. Igor had to deal with gang members (MS-13 and Barrio 18). Anastasia had a terrifying breakdown. The details of these first days are staggering.

What about the little boy, Vladimir, three years old at the time? The Kremlin was quick to weigh in. It did so in the person of Pavel Astakhov, who was then Putin’s commissioner for “children’s rights,” notorious. Astakhov declared that Vladimir was a Russian child who should be in the hands of Russian authorities. (Tough luck, Pavel: The Guatemalan-born Vladimir is a Guatemalan citizen.) Irina and Igor wanted their son to be in the hands of their chosen guardians: his longtime nanny and one of the family’s lawyers. A judge sent him to an orphanage.

He was there for 42 days. When he was finally released to his guardians, he was in very bad shape, physically and mentally. He had a scar over his eye. He had a respiratory infection and an ear infection. He had conjunctivitis in both eyes. He had a chipped front tooth. He was undernourished. Moreover, he was in a zombie-like state, unable to speak. In fact, he forgot how to speak Russian altogether.

Today, Vladimir is in good shape, all things considered, cared for by those remarkable guardians. At Mariscal Zavala Prison, I meet him briefly outside the women’s facility, where his mother and sister are kept.

In our separate interviews, the prisoners — Igor, Irina and Anastasia — tell me repeatedly how grateful they are for their clutch of helpers and advocates, whom they refer to unblushingly as “angels.”

Igor has been in prison since the day of his arrest in January 2015. For a year — from January 2015 to January 2016 — Anastasia was in hospital detention, along with her mother. They were then released under house arrest (which lasted until January of this year). Sometime during 2015, when the Bitkovs were away, their house was looted, almost certainly by the police, who were responsible for guarding the house. Everything was taken — even Vladimir’s toys.

It is very important to Anastasia and her family that she stay out of a place called Federico Mora Hospital. (Not the hospital she was detained in, which is called Concepción.) A warden, among others, has threatened to send her to Federico Mora. It is a mental institution that consigns girls and women to sexual slavery. The BBC did a documentary on it with a blunt title: “The World’s Most Dangerous Hospital.” Mariscal Zavala, where Anastasia is now, must be very heaven by comparison.

Last December, one court ruled that the Bitkovs were not guilty of any criminal offenses. If anything, they were guilty of administrative offenses in the matter of their passports and ID cards, which might make them liable to a fine. But CICIG et al. challenged this ruling — and the Bitkovs were convicted. Their sentences: 19 years in prison for Igor, 14 each for Irina and Anastasia. For passport violations and documentary irregularities.

The sentence for rape is between eight and twelve years. Murderers rarely get what the Bitkovs got. There are people in this country, and elsewhere, who are anti-Bitkov: who buy the Russian propaganda or simply scorn the family. But virtually no one thinks their sentences are anything but insane and shocking.

I will quote CICIG, through its spokesman Matías Ponce, who in the below paragraph is speaking of CICIG’s efforts against a crime ring — a network composed of the aforementioned government officials, traffickers, and the like. In CICIG’s view, the ring includes the Bitkov family, as “users” of it.

The Migration Case was internationally praised for having dismantled a large network that posed a risk to national and regional security. Proceedings were conducted under Guatemalan law, including all constitutional and procedural safeguards. All those prosecuted enjoyed right to defence and were free to act on all available actions (appeals, human rights safeguards, etc). The Attorney General’s Office, with support from CICIG, fulfilled its role to file charges and provide evidences, always under Guatemalan law. In Guatemala, after hearing the defence and the prosecution, Judges are independent to rule and set penalties within the limits of the Criminal Code. The case remains open, currently pending two different appeals by higher courts.

Before seeing Irina and Anastasia at Mariscal Zavala, I see Igor. The men’s facility is like a tent city or shantytown. Igor points to one of his fellow inmates and says, “He’s a judge” (or was a judge). In Guatemala, Mariscal Zavala is known as a “VIP prison.” Yet you and I would not want to live here, trust me.

One look at Igor and you know he’s keeping himself in very good shape. He looks like an athlete. He exercises regularly. This is important for his mental health, he says. It helps chase the darkness away. Also, he wants to keep himself fit for his family’s sake. He thinks of Vladimir: How old will this boy be when his father gets out? How old will the father himself be? He is aiming for longevity. He wants to be around.

Ever the entrepreneur, Igor is making and selling crêpes to his fellow inmates. What kind of crêpe do you want? He can make you almost any kind. He once ran a $450 million pulp-and-paper company. The crêpe business in prison is a lot humbler, but still something.

When I ask him about his spirits — his mental health — Igor says, “I believe in God.” He is Orthodox, and he participates in services here with Catholics and evangelicals.

What would he like people to know, about what has happened to him and his family? This: “The Kremlin has tremendous power. More than people realize. More than I realized, before we were persecuted here in Guatemala. This is secret power, not in evidence. The United States has power, but it’s clear, transparent. The U.S. is a big democratic country.”

Igor believes that the Russian influence on his fate is strong, and that Guatemala is awash in Russian money and schemes. “Russia is a criminal state that corrupts others.” He is far from alone in this belief.

In the women’s facility, conditions are worse for Irina and Anastasia than for Igor. The prison is very cramped, with bunks giving people just a sliver of privacy. But at least the prison is not violent. (The men’s, too, has the advantage of non-violence.)

“I have been in survival mode for years,” says Anastasia. She is gracious and composed. She has embraced Christianity, and in fact was baptized just yesterday. “God is healing me. He is doing His work. That is why I can walk around smiling, despite being sentenced to 14 years in prison. You need to lose everything in life to come to the understanding that you never had anything at all. It was all an illusion. Real life is not physical — it comes from within.”

What Anastasia has been through is mind-boggling. During the drama of the last few years, she got married, to a Guatemalan who is now in Spain. His petition for divorce and her sentence of 14 years came on the very same day: January 5, 2018. I laugh when she tells me this. I ask her to forgive me, and she does. She laughs, too. You almost have to.

As for Irina, she believes that “God has some mission for us.” She also says that she has a goal, which she calls a “dream”: to be part of a team that helps others who are trapped in nightmarish circumstances, such as those she and her family have faced.

Russian authorities continue to taunt and haunt the Bitkovs. They are intent on prosecuting the family in Russia, and they talk of extradition. (Vladimir’s Guatemalan citizenship is a problem for them.) Every day in the state media, they make villains of the Bitkovs. Anastasia says, starkly, “There are people in Russia who believe that we deserve not prison but death.” The Bitkovs believe, and their supporters believe, and experts on Russia believe, that the Bitkovs’ return to Russia would mean their death, their murder.

Irina’s mother and Igor’s brother have visited the family here in Guatemala. Afterward, their homes were raided: Irina’s mother’s in Arkhangelsk and Igor’s brother’s in St. Petersburg. “They took every electronic thing,” says Igor, referring to agents: computers and phones. “They interrogated them for hours, and threatened to put them in prison.”

Six-year-old Vladimir may be Guatemalan, but Igor, Irina, and Anastasia are citizens of no country. Anastasia cites an old term for their status, “civil death.” The family is amazed that people in Guatemala and elsewhere are willing to help them: “not because we are their fellow citizens,” says Irina, “but simply because we are human beings.”

Prominent among these helpers is Bill Browder, the financier who became a human-rights advocate when his lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, was tortured to death in Russia. Browder has spearheaded “Magnitsky acts,” which are laws that sanction human-rights abusers in Russia. He makes an interesting point (and, to me, a persuasive one). It is as follows.

In March, the Russian state tried to murder Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, in Salisbury, England. This was the poison attack that received worldwide attention. Sergei Skripal was an officer in Russian military intelligence and a spy for the British. He was, in short, a double agent. He went to Britain in a swap between the two countries. The Russians don’t really care about Skripal (in the view I am stating). He is in no position to do any harm to them anymore. What they wanted to do is send a message to others: If you betray us, we will get you, even if you think you’re safe abroad. So it is with the Bitkovs (again, in the view I am stating). The Kremlin doesn’t give a damn about this little, tormented family. They are simply sending a message to others: If you defy us — if you’re a businessman who doesn’t hand over his assets willingly — we will find you and hurt you, no matter where you go. You want to end up like the Bitkovs?

Call it deterrence.

What can the United States do? Anything? Well, Washington is the biggest aid donor to Guatemala — by far — and it also pays for about half of CICIG’s budget. At a minimum, Congress ought to know about this bewildering and sickening case.