The Bitkov family were victims, not members, of a crime syndicate.

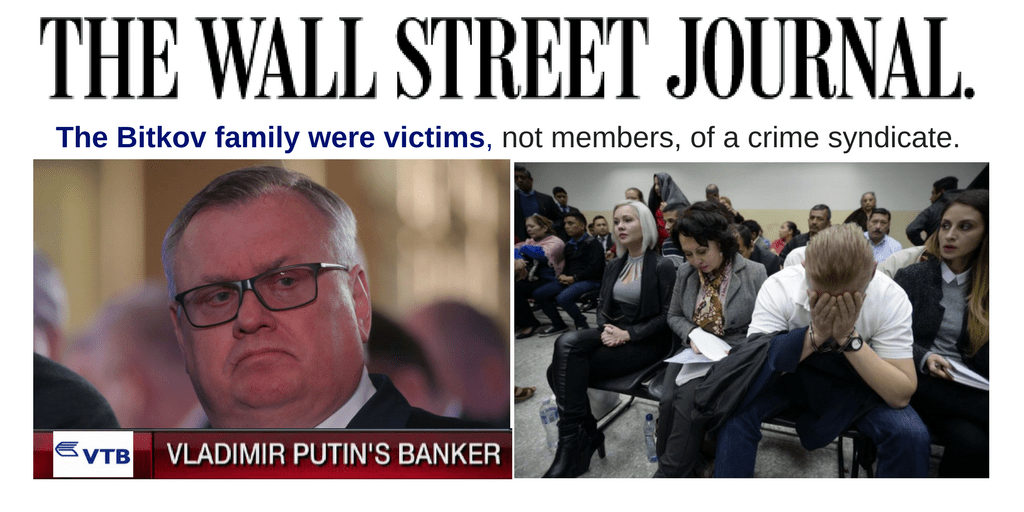

Andrey Kostin, chairman of Russia’s state-owned bank VTB and a Vladimir Putin ally, was in the news twice this month. On April 4 The Wall Street Journal published a letter to the editor from Mr. Kostin. He vented in the letter about my March 26 column detailing his vendetta against fellow Russian Igor Bitkov in Guatemala. He claimed the column “perpetuates an inaccurate portrayal of Russia’s banking industry and its state banks.” The next day the U.S. Treasury imposed sanctions on Mr. Kostin and six other Russian oligarchs.

A Treasury spokesman told me last week in an email that the sanctions are “a message” that the U.S. won’t “tolerate the Russian government’s ongoing malign activities around the world.” That got me thinking about the Inspector Javert-like intensity with which Mr. Kostin is tracking Mr. Bitkov, and how Guatemalan prosecutors and some judges seem to have suspended legal norms to punish the target of the Russian banker’s ire.

In January a Guatemalan tribunal handed unusually harsh prison sentences to Mr. Bitkov (19 years), his wife, Irina, and their daughter Anastasia (14 years each) for using false documents provided to them by government offices. The United Nations Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala—CICIG by its Spanish initials—was set up to strengthen the rule of law but took part in this travesty. The Bitkov case looks more like human-rights abuse in the interest of a high-ranking Russian. CICIG’s complicity is troubling.

Mr. Bitkov’s difficulties began in 1999 in the infamously corrupt Russian region of Kaliningrad, where he bought a paper mill to expand his North-West Timber Company. Mr. Bitkov says a Putin minion asked to buy 51% of the company in 2005. He declined.

Mr. Kostin’s letter says that Mr. Bitkov had not “been actively involved in Russia’s political or social matters.” Mr. Bitkov agrees. When Putin’s United Russia Party tried to enlist Irina as party chief in Kaliningrad in 2007, she declined, according to Mr. Bitkov. He says she also turned down an offer to join the board of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, where Mr. Kostin is chairman. These posts typically require very large “dues” payments. The Bitkovs wanted to put their money toward the business. Putin henchmen asked for millions of dollars in “donations”; the Bitkovs said no.

In 2007, 16-year-old Anastasia was kidnapped and raped. A $200,000 ransom payment from the family secured her release. The Bitkovs believed there was a link between the kidnapping and their resistance to what was essentially an extortion racket run by a Putin political mob in Kaliningrad.

They went to Austria on April 14, 2008, hoping to return when things cooled off. But two weeks later three state-owned banks that had lent them money demanded immediate repayment. Through his lawyer in Guatemala, Mr. Bitkov told me that the family returned in May to negotiate with the banks. But they were warned by an official that an arrest warrant had been issued and they fled again. They arrived in Guatemala in April 2009.

Mr. Bitkov says the company was forced into bankruptcy and sold for a song. Mr. Kostin wants us to believe that the Bitkovs deliberately destroyed their successful $428 million company so they could run away to Guatemala with $6 million.

That’s the amount of the loans that VTB alleges Mr. Bitkov guaranteed personally. Mr. Bitkov says VTB’s documents are forged, so the court asked VTB for the originals. VTB did not produce them. Instead it switched its line of attack, arguing that the matter could be resolved only in Russia. There is no proof of VTB’s money-laundering charge either, which is why prosecutors lack grounds for indictment.

In 2015 Guatemala’s attorney general indicted the family for using government-issued falsified documents. In December a constitutional appeals-court ruled that the Bitkovs had committed only administrative offenses, not crimes. Two days later, according to the family, Russian police raided the homes of Irina’s 68-year-old mother in the Arkhangelsk region and Igor’s brother in St. Petersburg. The two were threatened with imprisonment if they continued sending money to their loved ones in Guatemala.

Mr. Kostin’s letter references 36 others convicted along with the Bitkovs. Yet all those were part of a crime syndicate providing false documents—many working for the government. The Bitkovs were the only defendants who were victims of the syndicate. Under the U.N.’s Palermo Convention and Guatemalan law, they should have been treated as such.

I asked CICIG press officer Matias Ponce in an email why the Bitkovs were not treated as victims and why the law firm that processed their applications was not investigated. Mr. Ponce declined to answer my questions.

Mr. Kostin refuses to recognize the appeals-court ruling. That’s predictable. More disturbing is CICIG’s failure to object to the lower-court tribunal’s decision to sentence the Bitkovs anyway. It’s another question to CICIG that went unanswered.

Write to O’[email protected].